The Michigan billionaire’s confirmation hearing was heavy on partisanship and light on substance.

This story was updated on September 8, 2017.

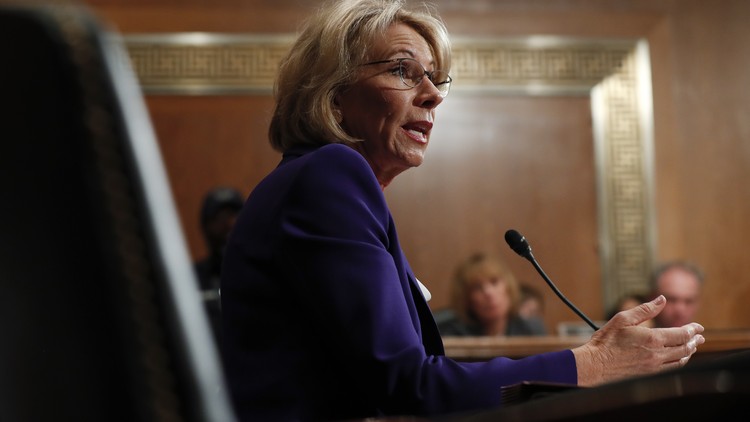

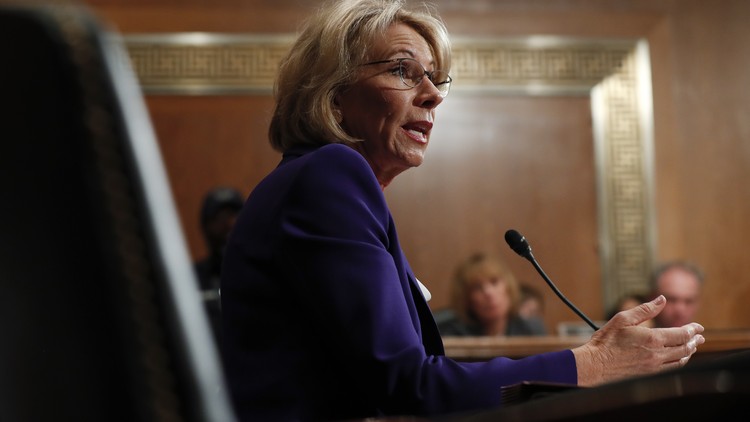

Donald Trump advocated on the campaign trail for a $20 billion federal school-voucher program. But during her confirmation hearing on Tuesday evening, Betsy DeVos, the president-elect’s choice to lead the U.S. Education Department, said school choice should be a state decision. She framed school choice as a right for students and families. And she said during the hearing that she was committed to strengthening public education for all students.

While the Michigan billionaire has backed charter schools and vouchers, which let families use public money to pay for private schools, DeVos would not, she said, try to force states to embrace school choice. But a number of organizations, largely Democratic, that had raised questions about DeVos’s commitment to expanding charters and vouchers and about her family’s financial holdings and religious causes were unlikely to find much more of the hearing reassuring.

Throughout the three-hour-plus exchange between DeVos and members of the Senate’s Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, DeVos—who has never taught public school, never attended public school, and never held elected office—sidestepped questions about everything from how she will ensure that groups she has backed financially in the past will not feel pressure to behave a certain way to whether guns belong in schools. At one point, she seemed to suggest that a federal law governing how students with disabilities are educated could be left to states, prompting Democratic Senator Maggie Hassan to express concern about her grasp of the department’s obligations.

Noticeably absent from the hearing were substantive discussions of the Common Core standards, which Trump has lambasted; how DeVos would handle racial inequity and school segregation, which have been priorities of the Obama administration; and issues around standardized testing, accreditation, and for-profit schools. She offered little clarity around her views on higher education and early-childhood education, broadly. But she did push back at the idea that college is the only pathway to success, and indicated that she would support vocational schools and career-training programs—a nod to Trump’s voter base.

“She is and has been on our childrens’ side.”

The evasion tactics (which nominees of both parties have employed for as long as confirmation hearings have been a thing) left Democratic members of the committee calling for more hearings. The convening was more intense than most hearings in recent memory involving nominees for education secretary in part because DeVos is an unusual nominee. She and her family have vast financial holdings, and she is the first of Trump’s nominees to go through the hearing process without a signed ethics agreement in place for how she plans to resolve any conflicts of interest.

While the prominent Republican donor faced critical questions about those holdings and other education issues from senators such as Elizabeth Warren and Tim Kaine, she also received praise from Republicans, such as from the former education secretary Senator Lamar Alexander, who think Washington has overstepped its reach on education under the Obama administration. “She is and has been on our childrens’ side,” he said.

In the weeks leading up to the hearing, a number of prominent Republicans, including former presidential contenders Mitt Romney and Jeb Bush, came out in support of DeVos’s work to support school choice. But civil-rights groups and teachers’ unions have challenged what they see as her lack of experience in public education and her family’s ties to conservative religious organizations.

Broadly, DeVos has fought to expand charter schools and the use of vouchers, including to pay for religious schools. DeVos has spoken in the past about advancing a Christian agenda through education. And critics are worried that her involvement with a variety of causes and lawmakers will complicate her ability to serve as secretary.

According to the left-leaning Center for American Progress, DeVos’s family has given nearly $1 million to more than 20 senators who will vote on her confirmation, including roughly $250,000 to members of the education committee. The family gave Senator Tim Scott, the Republican from South Carolina who introduced DeVos at the beginning of the hearing, nearly $50,000, and he served as keynote speaker at last year’s annual summit for the American Federation for Children, an organization she chaired until recently.

In a 1997 op-ed, DeVos defended her family’s donations to the Republican party at the time on the grounds that such money would promote its priorities of limited government and traditional American values. “I have decided to stop taking offense at the suggestion that we are buying influence,” she wrote. “Now I simply concede the point. They are right.”

Some lawmakers have also raised concerns about her connections to certain industries she would oversee as secretary, among them student loans. As the Washington Post noted recently, DeVos has ties to a firm that loaned money to a debt-collection agency that did business with the U.S. Education Department. That agency, Performant Financial Corp., recently failed to win another bid with the department, but, as secretary, DeVos would be able to affect which companies win such contracts and how they are handled. DeVos said during the hearing she and her husband would distance themselves from such education investments.

In her opening statement, DeVos said, “I share President-elect Trump’s view that it’s time to shift the debate from what the system thinks is best for kids to what moms and dads want, expect and deserve.” She spoke of a visit when her oldest child was young to a Christian school serving low-income children, where she “saw the struggles and sacrifices many of these families faced when trying to choose the best educational option for their children.” That experience, she said, helped spark a commitment to school choice.

That’s a record that has won her favor not only with many Republicans, but with a few Democrats, too. Anthony Williams, the former mayor of Washington, D.C., and a Democrat, praised DeVos’s support of vouchers. The city has the country’s only federally funded voucher program, which Williams backed. And she was introduced by the former Connecticut senator Joe Lieberman, a Democrat who later became an independent. Lieberman sits on the board of the American Federation for Children, which DeVos chaired until recently.

Yet according to a 2015 PDK/Gallup poll, most Americans favor the idea of charter schools, but less than a third support the concept of vouchers. Many economists also question the idea of privatizing the U.S. education system. As Susan Dynarski, a professor of education, public policy, and economics at the University of Michigan noted in the New York Times recently, a panel of economists who generally support a free-market approach to things like ride sharing was not inclined to support the use of vouchers. In some cases, she writes, charter schools (publicly funded but privately run) that are closely overseen can create healthy competition for traditional public schools. But critics have pointed out that Michigan, where DeVos has concentrated many of her efforts, has some of the worst-performing, least-regulated charter schools in the country.

Senator Alexander, who chairs the committee, said it would meet early next week to consider DeVos’s nomination, provided her agreement with the ethics office is in place by Friday.